Churches

Relationships

Imagine that someone came to your work or home and told you about this amazing drug that would vaccinate you from the common cold (or something similar). How much would you be willing to pay for that drug? Would you take it at all? You don’t really know this person, they showed up claiming to be an expert, do you trust them? Suppose that you do trust them enough to believe that this drug at the very least will not do any harm to you. What would you be willing to pay for this drug? Most of us would probably be willing to pay $10 for a shot at preventing the cold. But what if the price was $50, $100, $500? As the price increases, the less likely we would be to buy the treatment.

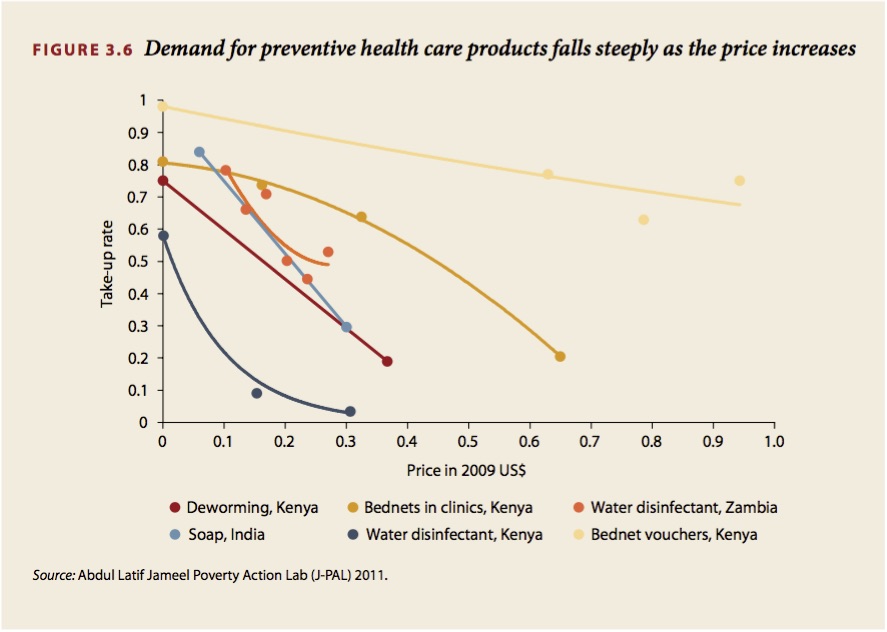

This may seem like a rather unlikely situation, but these are often the circumstances that people in developing countries often find themselves in. Rather than the cold, they have been pitched to by NGO’s and experts who claim to be able to provide relief from any number of diseases that result in far worse outcomes than a few days away from work. Despite these attempts to increase the usage of preventive medicines, several studies have shown that even when they are provided for free the uptake is still less than 100% (see figure 3.6).

The question is why does this occur? It's not that the poor do not care about good health, studies have shown that they spend 5% of their monthly budget on health services (compared to 6% in the United States). However, this spending tends to go towards expensive cures rather than cheap prevention. At some level, this behavior comes down to trust. It is much easier to draw a mental link between taking medicine and feeling better, than to draw the same link between getting vaccinated and not getting sick. How do you know that it works? Perhaps you have gotten lucky and not been exposed to the disease. You must trust that the prevention is working, that it is making some sort of difference. Notice this is not a situation that is dealt with in developed countries. The water that comes out of our faucets is clean, our houses are connected to sewage systems, trash collectors take away our garbage, we must get vaccinated to attend school, by in large we do not have to make choices to keep ourselves healthy. However, when you have to make choices like these to stay healthy, trust is an important component of taking on the cost.

This is why the local church is so important. By partnering with existing churches we can build on their established credibility (figure 4.7 shows that religious leaders are universally more trusted than government officials). At the very least we should be able to reach the members of the church and once these programs have been successfully implemented studies have shown that people are willing to purchase the product again even if they have to do so at full price. On top of that, other studies have shown that social learning is important in the adoption of new technologies and products. In other words, once people see these programs making a difference they will be more likely to use them themselves.

Location

The local church’s location within the community can help solve two issues that often plague medical care in developing countries: convenience and absenteeism.

Recently, there has been a concerted effort in developing countries to increase rates of immunization among children. The main problem that health workers have come across is that while immunization camps have been successful in delivering the first in a series of vaccinations to a large number of children, most do not complete the series. By in large, researchers have found that incomplete vaccinations are associated with the inconvenience of taking your child to a medical center or hospital (which are often located in excess of ten miles away from where the child resides) to receive or finish the vaccination process. Because the church is a location that at least the parishioners visit on a regular basis, the inconvenience of getting your child vaccinated is alleviated.

Absenteeism is also a large issue when it comes to providing medical care in developing countries. Often the health care practitioners simply do not show up to work. This is problematic on two fronts. First, when the clinic workers do not show up no medical care can be given. Second, because visiting clinics can often represent a significant cost to an individual in terms of travel time, the uncertainty in regards to someone actually being at the clinic to treat them may be enough to discourage them from seeking medical care. Under the traditional model it is difficult to correct this because those responsible for oversight are often several hours away by car. This problem is easily preventable as those responsible for oversight (the church) will be in direct proximity to the clinic.